Turkey’s Sustainability Issue After the Rating Upgrade – Part I

- Posted by Pelin Dilek

- Posted on May 19, 2013

- Macro Topics

- Comments Off on Turkey’s Sustainability Issue After the Rating Upgrade – Part I

After twenty years, Turkey is finally rated investable by two-rating agencies. Even though Moody’s upgrade on May 16th upgrade was largely expected, it deserves attention for its impact on Turkey’s long-term structural issues.

First part of this essay, which is posted below, argues that the level current account deficit has reached in Turkey puts external debt sustainability into the radar. Instead of focusing on energy deficit as a reason for the current account deficit, it is argued here is that the fall in the real interest rates via its impact on the savings ratio is linked to the current account deficit.

Part two of the essay points out the need for the Turkish economy to increase its investment ratio as to be able to raise the value added of the domestic production and hence exports. The need to increase investments makes long-term sustainable financing a key factor for success. Long-term sustainable financing can be ensured by increasing domestic savings ratio higher and/or by making the current external borrowing mix cheaper and longer-maturity. Therefore, the recent rating upgrade should have a positive impact on external debt sustainability calculations. Yet, the ideal situation would be the acceleration of foreign direct investments, as a non-debt creating flow until when higher level of investments results in lower current account deficit figures. In this respect, the impact of the rating upgrade is more limited as FDI decisions are not necessarily restricted by the sovereign ratings as much credit and portfolio flows are.

Part I: Focus Shifts from Domestic to External Debt Sustainability

Throughout the latter part of 1990’s and 2000’s, the most important issue for the Turkish economy was the sustainability of domestic debt. With ever-growing budget deficits in the 1990’s and recapitalization of the financial sector in 2001-2004, public domestic debt to GDP ratio soared above 70%. As a good example of expansionary fiscal austerity, primary surpluses and positive GDP growth rates have been detrimental in Turkey in reversing the course of public debt dynamics for the past ten years.

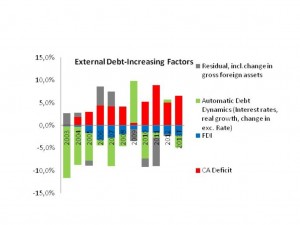

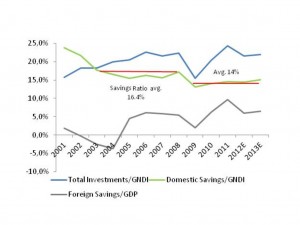

Turkey’s current sustainability focus, on the other hand is the external debt side. Turkey’s external debt stock by the end of 2012 was 43% and two thirds of it belonged to the private sector. In terms of ration of GDP, external stock level is not alarming but it is important that Turkey’s current account deficit is putting an increasing burden as a debt-creating flow and it is a source of potential instability for the economy.

Investments are increasingly financed by foreign savings in Turkey…

In order to understand how the current account deficit reached the current high levels, looking at the relationship between current account deficit, investments and savings helps. As the investments equal savings in any given economy, the difference between the country’s investment and domestic savings has to be filled with foreign savings, which is represented on the capital account side of the balance of payments. These capital transfers can be in the form foreign borrowing (debt-creating flow) as well as foreign direct investments (non-debt creating flow). Put differently, difference between investments and savings should equal the current account balance, which the capital account finances. Ideally, investments geared towards raising the value added of production should help increase exports and decrease the current account deficit over time; or with the increased value added within the country, disposable income rises and savings increase, again decreasing the need for foreign savings.

In Turkey, investments/GDP ratio traditionally hovered around 20-23% since the 1990’s. The only exception was between 2002-2004 when the average investment/GDP ratio fell to 18% following the 2001 crisis. While domestic savings met almost all of the investment need during the 1990’s, starting with 2004, we have started observing a fall in savings ratio below 20%. In order maintain the investment demand of above 20% of GDP, Turkey started relying increasingly on foreign savings; resulting in high current account deficits. As the savings ratio fell to another lower plateau in 2009, Turkey experienced a surge in foreign savings, carrying the current account deficit close to 10% of GDP by the end of 2011.

There is a link between current account deficit and real interest rates

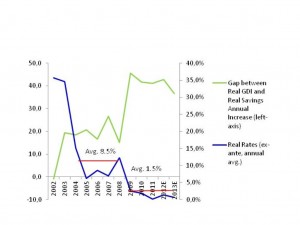

A World Bank report dated December 2011 (Sustaining High Growth: The Role of Domestic Savings Synthesis Report), analyzes in detail the determinants of savings rate Turkey: Gross private disposable income, young age dependency ratio, and the inflation rate explain well the private saving behavior in Turkey. The report also lists precautionary motives, life cycle events, higher female employment as the determinants for private savings. But of the list, real interest rates seem to be the factor, which has the highest impact:

The graph below plots the real rates against the difference between the real gross disposable income and savings real annual increase. For reasons of simplicity, disposable income and the real savings are both indexed to 100 in 2002, here. The graph shows that the gap between disposable income and savings widen especially after 2009 when the real interest rates fell to an average of 1.5%. In other words, private sector did not increase its savings as much as its income once the real interest rates fell.

To be continued in part 2…

- March 2023

- February 2023

- September 2022

- April 2022

- February 2021

- June 2020

- March 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- October 2018

- August 2017

- June 2017

- February 2016

- October 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- September 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013